Why Some Pet Food Recipes Can't Cross Borders

When your recipe travels, the ingredient list might follow. That’s the hidden danger of exporting pet food: the United States and European Union have very different regulatory philosophies.

In the US, pet food ingredients are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). Many ingredients are approved for use in pet food by the FDA through the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) process, which relies on expert consensus regarding the safety and utility of the ingredient. Essentially, in the US, unless an ingredient is explicitly restricted for use in pet food by the FDA CVM, it is generally considered safe and acceptable to use.

In the EU, however, it works in reverse. Under Regulation (EC) No. 1831/2003 and related feed laws, every additive used in food or pet food, whether a colorant, flavor, or probiotic, must appear on a list with a detailed scientific opinion from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Anything not specifically authorized is, by definition, illegal. The EU applies the precautionary principle, meaning that even the smallest concern of genotoxicity or long-term risk is sufficient to block or withdraw approval.

For added context, genotoxicity refers to the potential of a substance or ingredient to cause damage to the genetic material within a cell, which can lead to mutations or carcinogenesis (the transformation of a normal cell into a cancerous cell).

This difference: historic use and “generally safe” on the US side and explicit pre-market authorization on the EU side, explains why some ingredients flow freely in St. Louis but hit a wall in Stuttgart, and why the reverse can also be true. Let’s look at four key ingredients that illustrate the divide in each direction, and a case study of one that may soon move from “allowed” to “not so fast.”

Photo by OlhaRomaniuk

Ingredients Allowed In The US But Not In The EU

Smoke flavor is the liquid or powdered essence of wood smoke, condensed and filtered, used to impart a grilled aroma to food. In pet food, it is added purely for aroma and marketing appeal: to give a chicken-meal kibble the scent of roasted chicken, or to make a plant-based chew smell like bacon. The commercial use of smoke flavor in US-based treats and dry foods has been prevalent for decades. However, only a handful of individually authorized “primary smoke products” may be used in animal feed in Europe. Going further, several are being phased out after EFSA concluded that genotoxicity cannot be ruled out.

The concern is that smoke condensates naturally contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a group of combustion byproducts that can damage DNA and have been linked to cancer in laboratory studies. Due to these findings and a precautionary regulatory philosophy, the European Commission has declined to renew many authorizations for smoke flavors in human foods.

Synthetic colorants, the Food, Drug & Cosmetic dyes commonly seen on human food labels, tell a similar story. Red 40, Yellow 5 and 6, Blue 1 and 2, and Green 3 are still permitted in US pet foods when used and labeled in accordance with FDA and AAFCO rules. The job of these dyes is not nutrition, but optics: they transform extruded brown kibble into a more “meaty” red, or change round brown kibbles into green shapes that resemble peas. Pets are indifferent to the color, but the owner sees “real beef and vegetables” even when the product may be mostly starches and meat meals.

These dyes have been part of American human and pet food manufacturing for decades. In Europe, by contrast, most of these synthetic dyes are not authorized for pet food at all. The EFSA and the European Commission have either never approved them or have sharply limited their use because of potential links to hyperactivity, allergic reactions, or carcinogenic impurities in humans. Only a short list of natural pigments and certain iron oxides are approved.

The regulation of ractopamine illustrates how a feed additive for livestock can matter even when it isn’t sprinkled directly into pet food. Ractopamine is a beta-agonist that promotes lean muscle growth in pigs and cattle. The US has permitted its use in these species for decades, establishing residue limits and monitoring compliance. The EU, however, maintains a zero-tolerance ban. Following EFSA’s 2009 assessment, which found insufficient evidence to establish a safe intake, the Commission and member states prohibited its use in food-producing animals. Any pet food that sources meat or animal by-products from livestock-fed ractopamine cannot be sold in Europe without major supply-chain changes. The molecule never touches the kibble bin, but its presence upstream makes the difference between an exportable and a non-exportable recipe.

Ethoxyquin is a synthetic antioxidant that has been used since the 1960s to keep fats from turning rancid and to stabilize pigments and vitamins. It is prized in fish meals and high-fat diets for its ability to extend shelf life. In the United States, it remains permitted for use within specified limits. Europe initially allowed it too, but growing concern over an impurity called p-phenetidine and a lack of robust animal and consumer safety data prompted EFSA to issue a negative opinion. The European Commission suspended its authorization in 2017 and later confirmed a ban across all animal species, including pets. Here again, what counts as a long record of safe use under US law was not enough to satisfy EFSA’s demand for demonstrated safety.

Photo by eelinstudio

Ingredients Allowed in Europe but Not (Yet) in the US

Regulatory asymmetry cuts both ways. Some ingredients have cleared EFSA’s demanding process and are routinely used in European pet food, but lack an AAFCO definition or GRAS designation for dogs or cats, which means they cannot be used in US pet foods and treats.

Certain insect proteins are a striking example. The EU has authorized several species, including black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens), mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and crickets (Acheta domesticus), as protein sources for pet food, provided that hygiene and nutritional criteria are met. These approvals date back five to eight years and have enabled a vibrant European market for insect-based food and treats, prized for their sustainability, amino acid profiles, and some functional attributes such as antimicrobial properties. In the United States, AAFCO approved the use of black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) in adult dog foods in 2022, and the use of dried mealworm ingredients in adult dog foods in 2024. While crickets are now considered GRAS as a protein source for dogs, these insects are still not approved in All Life Stages type foods, or in cat foods altogether. The science of insect protein is not the obstacle; rather, it is the slower US regulatory pathway, which recent regulatory changes have further slowed.

Botanical extracts used as flavorings provide another example. Europe maintains an extensive list of authorized plant-derived flavoring compounds: herbs, spices, and essential oils, each with a FLAVIS number and defined inclusion limits for cats and dogs. These are used for their medicinal properties and to support natural and clean-label marketing. In the US, a plant extract can be used only if it already has an AAFCO definition or a GRAS designation. Many botanicals familiar to European homes and formulators are currently unlisted in the US, making them off-limits despite a long record of safe culinary use in other parts of the world, but with insufficient use and history in the USA.

Specific probiotic strains have also progressed more rapidly in Europe. The EFSA has approved multiple named strains—for example, in 2015, Enterococcus faecium DSM 10663/NCIMB 10415 as a zootechnical additive for cats and dogs with well-documented effects on gut flora stability. These authorizations often date back more than a decade. In the United States, each strain requires its own GRAS designation or AAFCO definition for use in pet food. Until that paperwork clears, a European formula rich in beneficial microbes cannot be reproduced for the US market without reformulation.

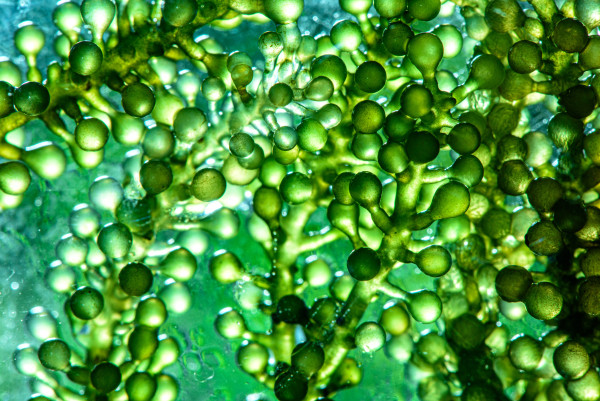

Novel algae-derived ingredients, particularly certain species cultivated for Omega-3 fatty acids, Beta glucans natural pigments, round out the list. The EFSA has approved oils from microalgae, such as Schizochytrium sp., Euglena gracilis and Odontella aurita, for use in animal feeds, including those for pets. The US has accepted only a subset of algae oils for animal feed, including Schizochytrium sp. and some other species and use cases still lack formal GRAS notices or AAFCO definitions. Again, the difference is regulatory timing, not a fundamental scientific dispute.

Photo by ckstockphoto

Titanium Dioxide: A Case Study in Rapid Change

One food additive deserves a special sidebar because it shows how quickly an ingredient can move from “commonplace” to “questioned.” Titanium dioxide (E171) is a whitening agent that has been used for a long time to brighten coatings on treats and to give kibbles a uniform, opaque appearance. (Fun or not so fun fact: it’s also being used to make paint white!)

In 2021, the EFSA concluded it could no longer be considered safe as a food additive because a genotoxic effect could not be ruled out. The European Commission banned its use in human food the following year.

While not all European pet food applications for the ingredient are explicitly prohibited, the consumer expectation has already spread to the companion animal sector. In the United States, titanium dioxide remains legal in both human and pet food when used within the limits set by the FDA. But with the EU ban and growing global scrutiny, many international brands are already phasing it out to stay ahead of future restrictions and consumer concern.

What This Means For Pet Food Innovators

Understanding ingredient status and regulatory differences is more than an exercise in compliance. It shapes everything from sourcing and formulation to labeling and marketing. A recipe developed in France may require costly reformulation before it can be sold in the US. Supply chains must be segregated if meat or fat from animals treated with ractopamine is involved. Marketing copy touting “smoked bacon flavor” may need to disappear entirely. Conversely, a probiotic-rich or insect-based diet popular in Paris might not appear on a New York shelf until years of petitions and approvals are complete.

The most forward-thinking brands are already designing for the strictest market they may one day serve. They audit every additive against both EFSA and AAFCO standards, swap out synthetic dyes for natural pigments, and question whether smoke aroma or bright-white coatings really add value to pet health. Partnering with experts who track both rule books can help agile brands be proactive, saving time and money in the long term, as well as avoiding expensive mid-stream changes.

In short, recipes can travel; ingredient lists cannot, unless you plan ahead. By understanding why US and EU regulations diverge and by formulating with the future in mind, pet food companies can streamline product development, simplify export, and build consumer trust on both sides of the Atlantic.

Follow us on LinkedIn for the latest updates on all things happening here at BSM Partners.

About the Author

Émilie Mesnier's passion for pets ignited during a 2007 internship in palatability research and has propelled her ever since. A French-trained food scientist, she now blends two decades of global know-how—nutrition, marketing, sustainability, animal welfare and international growth—into one goal: better foods and lives for animals. A lifelong learner who has absorbed insights from 80-plus business books on strategy and continuous improvement, Émilie turns ideas into action every day. After 16 years in the US and running a small farm animal rescue sanctuary in Utah, Emilie moved children, husband and two senior pets back to France in early 2025 to bring BSM Partners’ full suite of consulting services closer to clients across the European market.

This content is the property of BSM Partners. Reproduction or retransmission or repurposing of any portion of this content is expressly prohibited without the approval of BSM Partners and is governed by the terms and conditions explained here.