Buyer Beware: What Research and Resulting Media Got Wrong About The Farmer’s Dog’s Recent Study

Not all research is created equally, and not all of it rightfully earns the media attention it gets.

A recent scientific paper published in Metabolites on Oct. 17, 2025, is a perfect example of this scientific phenomenon. In the study funded by The Farmer’s Dog, a team of researchers compared a “fresh, human-grade” dog food to an experimental kibble diet to see how the different diets affected the dogs' bodies. Specifically, the study evaluated metabolomics, which is like taking a picture of what is happening inside the body’s cells.

The stated goal of the study was to “compare the effects of feeding a fresh, human-grade food versus a standard extruded kibble diet… on serum metabolomic profiles in senior dogs.” In other words, is fresh food better for older dogs than kibble?

While research like this is sorely needed, a closer look at the paper in question reveals major errors, missing details, design limitations, and oversights that make the study’s conclusions misleading and largely invalid.

The Design Was Flawed

Put simply, this study wasn't a fair test. The research aimed to understand if processing method affects dogs' health. To answer that question properly, you need to reduce the number of other factors that could have an effect, meaning the foods should have similar nutrients, just prepared differently.

But that's not what was done. Instead, the study compared two foods that differed in both processing and nutrient content. The “fresh” food had a significantly different nutritional profile than the kibble: more protein, more fat, way less carbohydrate, plus added Omega-3 fatty acids. These are two separate variables, and the study tested both at the same time without separating their effects. In scientific terms, the variables were "confounded,” or tangled together in a way that makes it impossible to know which one caused the results. Thus, any changes in the dogs' bodies were likely due to them eating completely different nutrients, not because one food was “fresh” and one was processed. It's like comparing a steak dinner to a bowl of cereal and claiming any differences you see are because of how the food was cooked, when really, you're comparing two totally different meals.

Additionally, the study used an experimental kibble diet, or one that isn’t available for commercial sale and wouldn’t be found in-store or online today. This means the experimental diet is simply that—a diet used in controlled research settings and not representative of the extruded kibble diets on the market that dogs are currently consuming.

The Data Is Unreliable

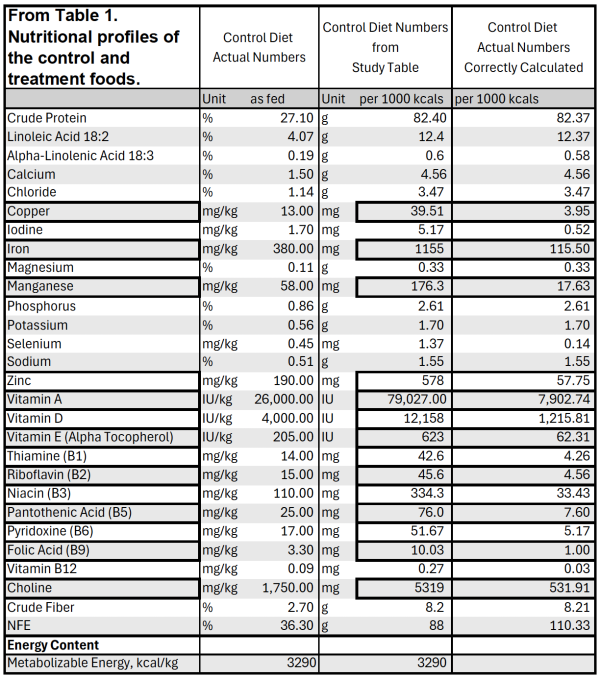

Glaring math errors in the Nutrient Table (Table 1, where nutrient levels for each diet are listed) reveal many important nutrients in the extruded kibble diet were reported significantly higher than they actually were—in some cases, 10 times higher.

For example, vitamin A was listed at 79,027 IU per 1000 calories, but the actual formulation technical sheet states it should provide only about 7,903 IU. Copper was listed at 39.51 mg per 1000 calories. Both vitamin A and copper, according to Table 1, were at levels that would exceed safety limits and potentially be toxic to dogs. Additionally, multiple minerals (including iron, zinc, and manganese) were reported at levels 50- to 100-times higher than nutritional minimums set by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), a body of regulators tasked with setting safety guidelines for nutrient levels in our pets’ food.

Based on publicly available documents from the company that manufactured the experimental kibble diet, these are systematic math errors that completely misrepresent what the dogs in the study actually ate, and hopefully just that; otherwise, the dogs fed these diets for a year could have experienced much more serious health implications.

When the basic facts about the diet are wrong, how can we trust any of the conclusions drawn from the study? The short answer: We can’t.

Key Details Are Missing

In addition to the concerns above, the research lacked transparency in several key areas. Good scientific studies provide enough information so that other researchers can repeat the experiment and verify the results. In this case, however, the research failed to provide enough detail, which is a major red flag for any study and should have been caught in the peer-review process.

For example, the research never explained how the “fresh” and “highly processed” diets were actually made, including how they were cooked, for how long, and at what temperatures. They also failed to disclose how much food the dogs were offered or how much they actually consumed. This matters because metabolic changes depend on what was eaten, not just what was provided. Further, it was unclear if nutrient levels for both diets were actually tested (sent to a lab to verify nutrient levels) or merely calculated (taken at face value from the recipe), as the math for vitamin A, copper, and several key minerals was flat-out wrong.

Lastly, some dogs received medications like antibiotics, thyroid medication, and pain relievers during the study, but the research did not clearly state when some of the dogs were given medication, at what doses, or which diet they were being fed (The Farmer’s Dog diet or the extruded kibble diet). These medications could have easily interfered with the dogs’ blood chemistry, which is precisely what the study was attempting to measure.

The ‘Fresh’ Dog Food Isn’t Even Fresh

The research described the test food as “fresh” and “minimally processed,” two terms that sound wholesome but have very specific meanings under federal food regulations. According to the FDA and AAFCO, “fresh” refers to food in its raw state that hasn’t been frozen, cooked, or otherwise preserved except through simple refrigeration. By those standards, the test diet in this study wouldn’t qualify. It was heat-cooked and packaged to ensure safety and shelf stability, which is exactly what regulations define as not fresh. Without explaining what they meant by “fresh” or “minimally processed,” the authors blurred the line between science and marketing, leaving industry professionals and pet owners with a false impression of what was really tested and why.

Not All Peer-Reviewed Research is Trustworthy

The peer-review process is undoubtedly important for maintaining scientific standards, but it isn't perfect. Studies with significant flaws can and do get published, especially in newer or less selective journals. This study made it through peer review despite systematic math errors in the nutrient table, a confounded design that couldn’t possibly have answered the stated research question, and missing methodological details, among other concerns.

It's important to look beyond the "peer-reviewed" label and ask: Does this study actually support its claims? Are there conflicts of interest? And what are the limitations?

The Bottom Line

While this study aimed to add to the currently limited body of knowledge that exists around fresh pet food, it failed to do so in a number of ways. Most notably, the research confused nutrient differences with processing differences, making it impossible to conclude that truly fresh or minimally processed food is better for senior dogs compared to kibble.

We can say dogs eating a high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet will have different blood chemistry than dogs eating a moderate-protein, moderate-fat, high-carbohydrate diet; this is expected and doesn’t tell us anything about processing methods. But because of the study’s flawed design, we can’t determine whether these differences were caused by processing method, by the diets’ differing nutrient profiles, or by some other uncontrolled factor.

For pet owners, this is a perfect example of why it's important to look critically at pet food research and media headlines. Ask yourself: What is the purpose of this study? Was the experiment fair? What were the study’s methods? And is there enough information for the study to be repeated? And, of course, are there any conflicts of interest? Good nutrition matters, but misleading science doesn't help anyone make informed decisions.

Learn more about what responsible research design looks like in this episode of the Barking Mad podcast.

Appendix I: Calculation Errors in Table 1

Appendix II: Regulatory Definitions of “Fresh” Food

According to the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) Official Publication (OP), as stated in “Chapter Six: Official Feed Terms, Common or Usual Ingredient Names and Ingredient Definitions,” the term “fresh” refers to: “ingredient(s) having not been subjected to freezing, to treatment by cooking, drying, rendering, hydrolysis, or similar process, to the addition of salt, curing agents, natural or synthetic chemical preservatives or other processing aids, or to preservation by means other than refrigeration.”

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 21, Part 101—Food Labeling § 101.95, “the term fresh, when used on the label or in labeling of a food in a manner that suggests or implies that the food is unprocessed, means that the food is in its raw state and has not been frozen or subjected to any form of thermal processing or any other form of preservation.”

According to The Farmer’s Dog, when asked what “fresh” means to the brand, it states: “Our meals are prepared in human food facilities, where each recipe is gently cooked at low temperatures according to human-grade standards. They’re then quickly frozen for safe shipping and your storage convenience.”

Thus, we believe The Farmer’s Dog diets are not fresh as defined by regulations.

Follow us on LinkedIn for the latest updates on all things happening here at BSM Partners.

About the Author

BSM Partners’ Nutrition & Innovation and Regulatory Services teamed up to summarize key points. Together, their combined experience in formulation, nutrition, research, and regulatory guidelines spans more than four decades.

This content is the property of BSM Partners. Reproduction or retransmission or repurposing of any portion of this content is expressly prohibited without the approval of BSM Partners and is governed by the terms and conditions explained here.